Hygiene and Sanitation

It’s estimated that 88% of

the households in India have a mobile phone but 732

million people do not have access to toilets or clean

sanitation. Sanitation is a basic right but unfortunately, this is one issue

which the country has not been able to handle in the last 70 years. Even in cities,

there is a dearth of proper drainage and disposal of waste. People still do not

segregate dry and wet waste, which causes huge issues in decomposing and

recycling. Continued usage of plastic leads to serious environmental and health

hazards which people despite of being aware about still chooses not to do

anything about it.

As per estimates,

inadequate sanitation cost India almost $54 billion or 6.4% of the country's GDP

in 2006. About $38.5 billion was health-related, with diarrhoea followed by

acute lower respiratory infections accounting for 12% of the health-related

impacts. Evidence suggests that all water and sanitation improvements are

cost-beneficial in all developing world sub-regions.

Sectoral demands for

water are growing rapidly in India owing mainly to urbanization and it is

estimated that by 2025, more than 50% of the country's population will live in

cities and towns. Population increase, rising incomes, and industrial growth

are also responsible for this dramatic shift. National Urban Sanitation Policy

2008 was the recent development in order to rapidly promote sanitation in urban

areas of the country. India's Ministry of Urban Development commissioned the

survey as part of its National Urban Sanitation Policy in November 2008. In

rural areas, local government institutions in charge of operating and

maintaining the infrastructure are seen as weak and lack the financial

resources to carry out their functions. In addition, no major city in India is

known to have a continuous water supply and an estimated 72% of Indians still

lack access to improved sanitation facilities.

A number of innovative approaches to

improve water supply and sanitation have been tested in India, in particular in

the early 2000s. These include demand-driven approaches in rural water supply

since 1999, community-led total sanitation, public–private partnerships to

improve the continuity of urban water supply in Karnataka, and the use of microcredit

to women in order to improve access to water.[7]

Total sanitation campaign gives strong

emphasis on Information, Education, and Communication (IEC), capacity building

and hygiene education for effective behavior change with involvement of

panchayati raj institutions (PRIs), community-based organizations and

nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), etc. The key intervention areas are

individual household latrines (IHHL), school sanitation and hygiene education

(SSHE), community sanitary complex, Anganwadi toilets supported by Rural

Sanitary Marts (RSMs), and production centers (PCs). The main goal of the

government of India (GOI) is to eradicate the practice of open defecation by

2010. To give fillip to this endeavor, GOI has launched Nirmal Gram Puraskar to

recognize the efforts in terms of cash awards for fully covered PRIs and those

individuals and institutions who have contributed significantly in ensuring

full sanitation coverage in their area of operation. The project is being

implemented in rural areas taking district as a unit of implementation.[8]

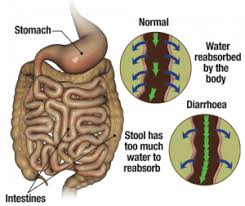

When sanitation conditions are poor, water

quality improvements may have minimal impact regardless of amount of water

contamination. If each transmission pathway alone is sufficient to maintain

diarrheal disease, single-pathway interventions will have minimal benefit, and

ultimately an intervention will be successful only if all sufficient pathways

are eliminated. However, when one pathway is critical to maintaining the

disease, public health efforts should focus on this critical pathway.[6] The

positive impact of improved water quality is greatest for families living under

good sanitary conditions, with the effect statistically significant when

sanitation is measured at the community level but not significant when

sanitation is measured at the household level. Improving drinking water quality

would have no effect in neighborhoods with very poor environmental sanitation;

however, in areas with better community sanitation, reducing the concentration

of fecal coliforms by two orders of magnitude would lead to a 40% reduction in

diarrhea. Providing private excreta disposal would be expected to reduce

diarrhea by 42%, while eliminating excreta around the house would lead to a 30%

reduction in diarrhea. The findings suggest that improvements in both water

supply and sanitation are necessary if infant health in developing countries is

to be improved. They also imply that it is not epidemiologic but behavioral,

institutional, and economic factors that should correctly determine the

priority of interventions.[7]

Another study highlighted that water quality interventions to the point-of-use

water treatment were found to be more effective than previously thought, and

multiple interventions (consisting of combined water, sanitation, and hygiene

measures) were not more effective than interventions with a single focus.[15]

Studies have shown that hand washing can reduce diarrhea episodes by about 30%.

This significant reduction is comparable to the effect of providing clean water

in low-income areas.[16]

Lack of safe water supply, poor

environmental sanitation, improper disposal of human excreta, and poor personal

hygiene help to perpetuate and spread diarrheal diseases in India. Since

diarrheal diseases are caused by 20–25 pathogens, vaccination, though an

attractive disease prevention strategy, is not feasible. However, as the

majority of childhood diarrheas are caused by Vibrio cholerae,

Shigellae dysenteriae type 1, rotavirus, and enterotoxigenic

Escherichia coli which have a high morbidity and mortality, vaccines against these

organisms are essential for the control of epidemics. A strong political will

with appropriate budgetary allocation is essential for the control of childhood

diarrheal diseases in India.[17]

Implementation of low-cost sanitation system with lower subsidies, greater household involvement, range of technology choices, options for sanitary complexes for women, rural drainage systems, IEC and awareness building, involvement of NGOs and local groups, availability of finance, human resource development, and emphasis on school sanitation are the important areas to be considered. Also appropriate forms of private participation and public private partnerships, evolution of a sound sector policy in Indian context, and emphasis on sustainability with political commitment are prerequisites to bring the change.

Comments

Post a Comment